Citation: Ganpat SM, et al. Violence Unfolding an Exploration of the Interaction Sequence in Lethal and Non-Lethal Violent Events. Psychol Pshycholgy Res Int J 2017, 2(3): 000127.

*Corresponding author: Soenita Minakoemarie Ganpat, Postdoctoral Fellow in Criminology, Department of Sociology, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, NG1 4BU, The United Kingdom, Tel: +44 (0)115 848 5512; Email: soenita.ganpat@ntu.ac.uk

Violent events typically entail an interaction between an offender, a victim and a context. Many of these events involve different stages which can be decisive, and some eventually end fatally. To better understand the mechanisms leading to a lethal or non-lethal outcome of violent encounters, this explorative study investigates the interaction sequence during these serious violent events. Based on detailed analysis of 160 Dutch court files, this study uses an innovative methodology examining the unfolding of events that ultimately resulted in a lethal or a non-lethal outcome. Findings show differences in the interaction sequence, and especially when the role of third parties and subtypes of conflict (i.e. male-to-male violence and male-to-female intimate partner violence) are considered.

Keywords: Sequence; Dynamics; lethal violence; Homicide; Male-to-male violence; Male-to-female intimate partner violence

It is an important challenge for homicide research to understand why violent events have a lethal outcome in some situations, and a non-lethal outcome in others. When addressing this issue, homicide research often focuses on offenders [1-5]. Other research draws attention to the dynamic nature of violent events [6-16]. Characteristics and sequence of the various stages of action largely appear to shape the outcome of interpersonal conflicts, whether violent or not. The present paper builds on this insight, focusing on the outcome of the dynamics during violent events. It does so by not only examining the importance of the escalation or de-escalation process, but also the actual sequence of actions during a violent event.

More specifically, this paper builds on the growing body of literature that suggests that (a) the types of action exhibited during conflict situations, and (b) the sequence (i.e., the chronological order) in which actions take place are highly relevant for the outcome of conflict situations [17-19]. For example, evidence from previous studies has indicated that the outcome of a (violent) conflict is more severe in cases involving types of action with a weapon by offenders or victims, physical violence by offenders or victims, or escalating actions by third parties (also known as bystanders) during the event [20-22]. However, these studies typically focus on the interaction sequence during either lethal violent events [11] or non-lethal violent events [23,24] and some only focus on non-violent disputes.

This present study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. Firstly, it contributes to the literature investigating the sequence of actions that eventually leads to lethal and non-lethal violence escalation [25,26]. Secondly, this study is one of the rare empirical studies that systematically compares the sequential process during violent events with a lethal and non-lethal outcome [20]. Thirdly, besides the offender and victim, this study also pays attention to other important – but often overlooked– actors when studying the sequence in lethal and non-lethal violent encounters; that is, third parties. Though the significance of third parties have been long recognized in field of the social psychology and criminology (e.g. see the literature on bystander effect as well as the role of guardianship in Cohen & Felson’s routine activity theory (1979)) [28], very few empirical studies focused on how third parties shape a lethal or non-lethal outcome of violent events. Fourthly, this paper distinguishes between two specific subtypes of conflict: male-to-male violence and male-to-female intimate partner violence (IPV). More precisely, we concentrate on the two main homicide subtypes in the Netherlands [29]: on the one hand, violent events occurring in the context of an argument or altercation between two males, and violent conflicts between intimate (ex-) partners on the other hand. The literature in many countries and cultures other than the Netherlands has also found male-on-male and intimate partner violence to be two of the most common subtypes of homicide [27, 30]. Several scholars have suggested that the type and sequence of actions might differ for these two subtypes of conflict [31]. In particular, the circumstances under which men harm or kill other men differ significantly from those under which men harm or kill their intimate partner. Although the importance of considering these subtypes of conflict has been stressed, virtually no empirical research has been conducted on how the type and sequence of actions differ across subtypes of conflict.

In short, what remains virtually untested is whether the type and the sequence of actions differ in violent events that ends lethally compared to those that end nonlethally. Examining the interaction sequence could yield fundamental insights into the mechanisms leading to a lethal outcome [32]. It may furthermore provide detailed insight into the actions and reactions of offenders, victims and third parties that potentially contribute to a lethal versus non-lethal outcome of violent events, and may in future even help stop the interaction chain from becoming lethal.

The present paper will therefore empirically examine the following research questions :(a) what are the types of actions and the sequence of actions during violent events that lead up to a lethal or non-lethal outcome, and (b) how do the type and sequence of actions differ across male-tomale violence and male-to-female intimate partner violence with a lethal or non-lethal outcome? These questions will be addressed by a detailed investigation of Dutch court files of 80 lethal and 80 non-lethal violent events that occurred in two large urban areas in the Netherlands using the most recent data available(i.e., years 2000-2009).

Theoretical Frameworks and Associated Empirical EvidenceSeveral theoretical frameworks – especially those influenced by symbolic interactionism – have pinpointed that conflict situations tend to follow a systematic, routine pattern in which several sequential stages can be distinguished in the process leading to a (lethal) violent outcome [11]. Building on Erving Goffman’s work, Luckenbill focuses on the development of interactions that lead to a lethal outcome in conflict situations. Luckenbill sees lethal violence as the result of a chain of interaction between the offenders, the victim, and if present, third parties, referred to as a ‘situated transaction’. He emphasizes the importance of perceived insults threatening one’s honor or face, which can eventually lead to a so-called ‘character contest’ between offender and victim (i.e., the use of violence as a means to show character in order to save or maintain face or reputation) [33,34]. By approaching a lethal outcome as a joint product in which the action of one individual shapes the action of the other, Luckenbill argues that it is not always clear beforehand who will end up the victim and who the offender .

Based on a content analysis of files concerning homicidal events, Luckenbill discerned six sequential stages forming a chain of interactions ultimately leading to a lethal outcome. In the first stage, the eventual victim performs a (verbal or non-verbal) ‘opening move’ that is perceived by the offender as an insult or personal offense that threatens the offender’s honor or face. Moving to the second stage, the eventual offender definitively draws the conclusion that the perceived insult by the victim was done deliberately. Then, in the third stage, the offender verbally or physically challenges the victim. According to Luckenbill, the fourth stage consists of a ‘working agreement’ between victim and offender, in which both parties accept that violence will be used to settle the dispute. The victim makes one of the following moves: (a) non-compliance and repeating the move that insulted the offender, (b) using physical violence against the offender, or (c) making a counter-challenge. According to Luckenbill, if third parties are present then it is in this stage that they either intervene in an escalating manner or remain passive. In stage five, the working agreement comes to a close. The victim or offender, or both the victim and the offender, make a lethal move. Eventually, the effectiveness of these moves determines the final outcome of the conflict; and it is in turn the outcome that determines who the victim is and who the offender [35].

In addition, relevant to the current study is Felson and Steadman’s sequential stage of (lethal) violence [20]. They confirmed that the sequential stages in (lethal and nonlethal) violent events largely occur as described by Luckenbill [11]. However, they added the element of retaliation. Retaliation often occurs not only because of face-saving concerns (honor), but also for strategic reasons (e.g., to defend oneself against the aggressive behavior of the other). Whereas cognitive aspects were also included in Luckenbill’s sequential stages, Felson and Steadman limited their analysis to behavioral stages instead, and also extended it by adding a new element which entailed included potentially de-escalating interventions by third parties, such as mediation.

In short, Luckenbill’s theory has been the subject of a large body of criticism concerning his gender-neutral assumption and the speculative nature of cognitive aspects in the working agreement-concept [36].

Empirical Studies on the Sequence of Lethal and Non-Lethal Violent EventsMany researchers have examined Luckenbill’s theory. Some studies on the sequence of events within violent encounters have focused mainly on non-lethal violent events. These studies have provided insight into how an offender perceives, interprets, defines or gives meaning to a situation, and into the situational decision-making processes that guide the offender’s actions. These studies do not, however, look at lethal violence [37].

Felson and Steadman however, examined both lethal and non-lethal events and found empirical evidence for the following sequential stages: the first stage starts with verbal conflicts involving identity attacks (e.g., insults, rejections, complaints or pushing without physical injury), and in which efforts to influence the opponent are unsuccessful (e.g., one person does not comply with another person’s demands to do something or to stop doing something). Subsequently, a second stage involves making threats (verbal threats or showing a weapon) and here, attempts can be made to avoid the use of violence, also referred to as evasive actions, which include “leaving the scene, fleeing, pleading for help, and apologizing”. Lastly, the third and final stage involves the physical attack. When Felson and Steadman compared violent events with a lethal versus non-lethal outcome, they did not find any statistically significant differences in the sequential stages of violence between these two types of events [20].

Empirical Studies on the Subtypes of ConflictNext, both Dobash and Dobash and Polk discuss the importance of looking at particular types of violent events when examining the sequence of action. For example, empirical support for Lukenbill’s stages was found by Dobash and Dobash, who focused exclusively on nonlethal intimate partner violence against females. Although the stages were largely corroborated, they did not find support for the so-called working agreement, as some victims in their study tried to avoid resorting to violence rather than accepting that violence was to be used [24,36].

Polk however, focused on male-to-male lethal violence and criticized that Lukenbill’s model predominantly applies to male-to-male violence where honor contest plays a key role, thus suggesting that the model is less applicable to male-to-female violence. To be more specific, according to Polk, male-to-female lethal violence often occurs when men attempt to control the behavior of their female partner. While male-to-male lethal violence commonly emerges as a result of the desire to ‘save face’, Polk suggested that possessiveness, authority, and jealousy play a more critical role in male-to-female cases instead (“If I can’t have you, no one will”) [36].

In sum, most empirical studies did not compare lethal events with non-lethal violent events and also did not devote attention to the sequence across different subtypes of conflict, and did not include potential deescalation attempts by third parties. The present study seeks to avoid these limitations, by (a) explicitly differentiating between lethal and non-lethal violent outcomes, (b) focusing on behavioral actions rather than cognitive aspects, (c) taking into account potential deescalation by third parties, and (d) considering both maleto-male violence and male-to-female intimate partner violence [20].

HypothesesBased on the literature and in relation to the first research question, we formulated a series of hypotheses regarding the type and sequence of actions leading up to a lethal versus non-lethal outcome.

Hypothesis 1a states that an action with a weapon by the victim will occur sooner in the sequence of actions in lethal cases than in non-lethal cases. This expectation is based on Felson and Steadman’s results, which found that aggressive victims, especially those who showed or used a weapon during violent events, were more likely to be killed than those who did not. The more aggressively the victim behaved, the more aggression the offender showed (e.g., inflicting greater harm by killing the victim) [11,16,20]. For example, in cases where the victim performs an action with a weapon sooner, the offender may perceive wrongdoing by his opponent sooner, increasing the urge to retaliate in order to obtain justice for wrongdoings, to save face or honor, or to defend him against the aggression of the other [15].

Given the finding of previous studies that escalation and de-escalation by third parties can also affect the severity of conflicts hypothesis 1b expects that escalating actions by third parties will occur sooner in the sequence of actions in lethal cases than in non-lethal cases. Hypothesis 1c postulates that de-escalation by third parties will occur sooner in the sequence of actions in non-lethal cases than in lethal cases. For example, if third parties show escalating actions sooner during the conflict, this may add fuel to the fire, encouraging the offender to cause greater harm (i.e., killing the victim). Similarly, an earlier de-escalation by third parties may deter the offender, potentially diminishing the likelihood of a lethal outcome [22,38].

Type and Sequence of Actions across Subtypes of ConflictIn addition, several hypotheses concerning the subtypes of conflict are formulated below, as the second research question is concerned with the type and sequence of actions in male-to-male violence versus maleto-female intimate partner violence.

Concerning the sequence of actions within each subtype of conflict, hypothesis 2a expects that physical violence – performed by either the offender or victim – will occur sooner within the interaction chain of male-tomale violent encounters than within male-to-female intimate partner violent encounters. This expectation is based on the reasoning that men are generally more violent than women and honor-related issues or the urge of showing stronger character might play a more pivotal role in conflicts occurring among men [39]. For similar reasons, hypothesis 2b states that an action with a weapon by either the offender or victim will emerge sooner in the interaction sequence of male-to-male conflicts than in male-to-female intimate partner violence. In addition, since researchers such as Dobash and Dobash have suggested that female victims tend to avoid the use of physical violence, hypothesis 2c expects that when female victims use physical violence, they will do so later in the sequence compared to male victims of male-to-male violence [24].

As for third parties, some evidence has indicated that they are less likely to be present during intimate partner cases than during non-intimate partner cases [40] and their presence increases conflict severity when the offender and victim are of the same sex [41]. Perhaps an escalating action by a third party could encourage the offender to use violence or increase the cost of backing down without losing face. Therefore, hypothesis 2d states that escalating action by third parties will occur sooner in the interaction chain of male-to-male cases than in cases of male-to-female intimate partner violence. Finally, hypothesis 2e expects that de-escalation by third parties will occur later in the chain during cases of male-tofemale intimate partner violence than during cases of male-to-male violence. In cases of male-to-female intimate partner violence, it is possible that third parties may be children who may not have the physical strength to adequately overpower the offender or may be more reserved, and thus less likely to intervene, out of fear. Also, since conflicts between intimate partners may be perceived as a private matter, third parties may initially be more reluctant to de-escalate [42,44].

Data and MethodsThe present research is part of a larger study on the role of personal characteristics of offenders and victims and immediate situational factors in shaping lethal versus non-lethal outcomes of violent events [2,3,7,8]. The present study uses a selection of the data of the Scoring Instrument (attempted) Homicide-study (SIH). In this study, systematic information on immediate situational factors was collected through detailed analyses of court files in a total of 267 serious violent events. Especially for the purpose of the current study, Dutch court files are a valuable source, as they enable a detailed examination of the interaction process during violent events with a lethal and non-lethal outcome.

The SIH dataset contains data on a selection of serious violent events with a lethal and non-lethal outcome, which were selected on the basis of the following criteria: (1) cases had to be registered in the court district of The Hague or Rotterdam (two of the largest urban areas in the Netherlands); (2) the offender had to be convicted for murder or manslaughter (i.e., intentional killing with or without premeditation, in accordance with Articles 287– 291 of the Dutch Criminal Code) or attempted murder or manslaughter (Article 45 of the Dutch Criminal Code in combination with Articles 287–291); (3) the case involved one offender and one victim; (4) both the offender and the victim were at least twelve years old at the time of the event; and (5) the court file was present at the court district during the data collection.

To compose the study sample for the present article, we used a selection of the cases included in the SIHdataset, by considering the sex of both the offender and victim and the subtypes of conflict. Based on the definition of subtypes of conflict formulated by Nieuwbeerta and Leistra we selected (1) arguments or altercations between friends, acquaintances, or strangers and (2) intimate partner violence against women by male partners, because these are two of the most prevalent homicide subtypes in the Netherlands [29]. Eventually, a total of 103 male-to-male cases were selected that entailed arguments or altercations between friends, acquaintances or strangers (39 lethal cases and 64 nonlethal cases), and a total of 57 cases of intimate partner violence against an (ex-) intimate female partner (i.e., male-to-female) (41 lethal cases and 16 non-lethal cases).

In the end, the sequence of actions within a total sample of 160 serious violent cases was examined (eighty cases resulted in a lethal outcome; the other half ended in a non-lethal outcome). Although the sample is of modest size, it is very rich in information as the court files have been investigated extensively and systematically in order to accurately reconstruct how these events evolved; see below.

MethodsCourt files: Examining court files is one of the few means of reconstructing the sequence of actions within different subtypes of serious violent incidents, and the role of third parties [11].

To analyze the court files, the SIH-study deployed a scoring instrument to systematically collect information about immediate situational factors, including the interaction between the offender, the victim, and third parties, during serious violent incidents. The researchers went to great lengths to arrive at an accurate reconstruction of what happened during these events, by consulting a wide range of documents including toxicological reports, eyewitness reports, outcomes of neighborhood investigations, police reports, autopsy or coroner’s reports, trace evidence, trial investigation reports, statements of the offender – and in the case of a surviving victim – victim statements [20]. Accordingly, rather than relying exclusively on offenders’ statements, all possible information in the files was compared and complemented constantly. In case of conflicting information, more objective sources that included expert assessments (such as toxicology reports, trial investigations, trace evidence or psychological reports) were favored over more subjective sources including the offender’s statement. All data were systematically gathered by eight specifically trained researchers using a scoring instrument containing detailed coding instructions. The interrater reliability rate was .78 indicating a substantial agreement between coders.

For each case, the course of events – as described in detail in the court files – was eventually summarized into a maximum of five ‘snap shots’, similar to scenes in a feature film. These snap shots helped to capture and reconstruct the actual sequence of events. The first scene depicts how the conflict started and the final scene pertains to the end of the conflict, i.e., the lethal or nonlethal outcome. Each scene represents a crucial moment in the unfolding of the incident and for each scene, a brief descriptive summary of actions was provided.

On the basis of this largely narrative information about the course of the event, we later created quantitative measurements, inspired by Felson and Steadman, which comprised information about (the sequence of) certain types of action, as discussed further below.

MeasurementsDependent variable

The dichotomous dependent variable comprised two conditions: either a lethal outcome or a non-lethal outcome.

Types of action: SIH researchers identified ten specific types of action, roughly borrowed from Felson and Steadman, Luckenbill, and Phillips and Cooney, indicating whether or not a specific type of action occurred at some point during the course of events, according to information in the case file. Each type is coded as a dichotomy, indicating presence or absence: (1) action with a weapon by offender; (2) action with a weapon by victim; (3) physical action by offender; (4) physical action by victim; (5) physical action by both offender and victim but unknown who started first; (6) verbal or non-verbal action by offender; (7) verbal or non-verbal action by victim; (8) verbal or non-verbal action by both offender and victim but unknown who started first; (9) deescalation by third parties (attempts to settle the conflict); and (10) escalation by third parties (worsening the conflict or taking sides) [22].

Sequential characteristics: Having coded each action in a case by type, we then arranged the actions of each case in chronological order, and coded nine variables according to the sequential characteristics of the actions of the case. These variables were largely inspired by Felson and Steadman and Wolfgang [16]. The first captured the total number of actions across the course of events in each case, and is a continuous number ranging from 1 through 10. The remaining eight variables are dichotomous, and are the following: (1) de-escalation by third parties during the last action; (2) de-escalation by third parties during the last two actions; (3) escalation by third parties during the last action; (4) escalation by third parties during the last two actions; (5) action with a firearm by offender during the last two actions; (6) action with a firearm by victim during the last two actions; (7) victim showing the first action in the sequence; and (8) offender showing the first action in the sequence.

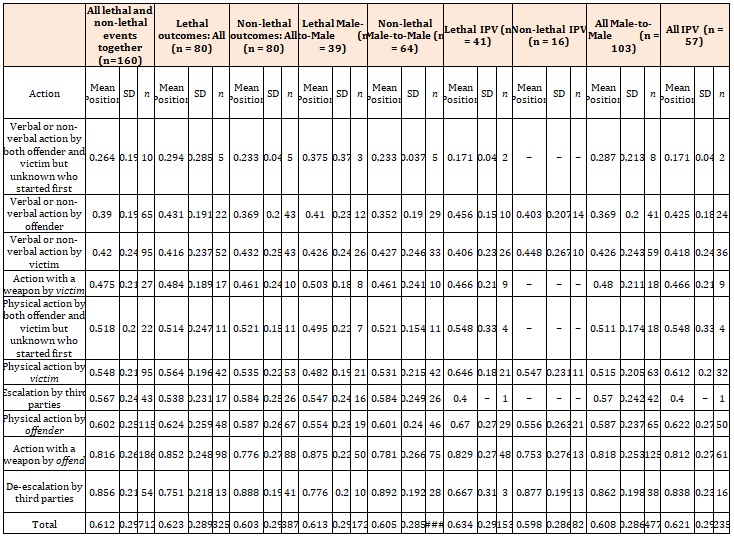

Sequence of actions: In further analyzing the sequence of actions, we took into account that incidents can vary as to how many types of action lead to a lethal or non-lethal outcome [20]. Comparable to the analytic strategy used by Felson and Steadman, the variable ‘position’ computes the proportion of the total number of actions for each action. For example, when four actions were coded in a case, the first was coded as .25, the second as .50, the third as .75 and the final action as 1.0. Thus, for every case the final action was coded as 1.0. In addition, we calculated the average (mean) position for each type of action.

Background Characteristics of Offenders and Victims:Four variables on background characteristics of offenders and victims were included: (a) sex, (b) age at the time of the offense, (c) birth country (1 = born in the Netherlands; 0 = born outside the Netherlands), (d) existence of prior criminal record of offenders and victims respectively (dichotomous), and (e) existence of prior violent record of offenders and victims respectively (dichotomous)

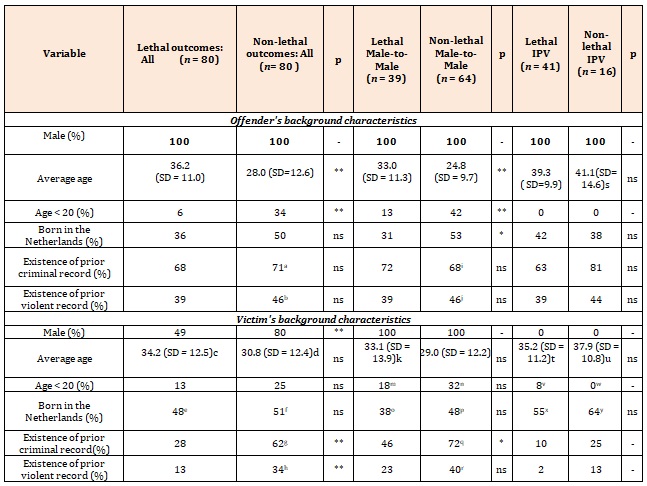

As displayed in Table 1, on average, offenders of lethal events were more likely to be significantly older but less likely to be under the age of twenty than offenders of nonlethal events. Victims who survived the events were more likely to be male and victims of non-lethal male-to-male violence were significantly more likely to have a prior criminal record, compared to victims of lethal male-tomale violence.

Table 1 also shows that when distinguishing between cases of male-to-male violence and male-to-female intimate partner violence, differences come to light especially in terms of: (a) the average age of offenders and victims, (b) the proportion of offenders and victims born in the Netherlands, and (c) victims’ prior criminal record. In particular, a far higher proportion of victims involved in male-to-male cases had a prior (violent) criminal record compared to victims of male-to-female intimate partner violence. It should be noted, however, that all of the victims in male-to-male cases were men and all of the victims in cases of intimate violence were women.

In the following section, we will firstly present the results concerning the types and the sequence of actions during lethal vs. non-lethal events (research question 1), followed by a more detailed analysis on how the type and sequence of actions differ across subtypes of conflict (research question 2).

ResultsIn light of our first research question and associated hypotheses, we compared violent events with a lethal versus non-lethal outcome with regard to the type and sequence of actions.

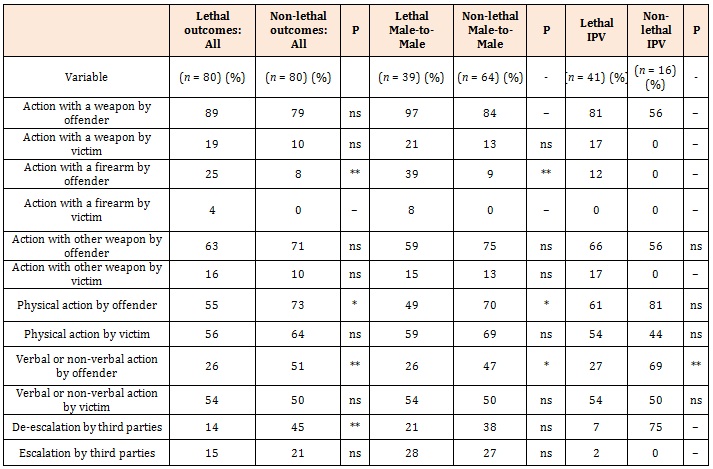

Types of Action in Lethal Versus Non-Lethal EventsThe frequency of the type of actions during lethal and non-lethal events is presented in the first part of Table 2. During lethal events it was more likely that the offender performed an action with a firearm but less likely that the offender showed a physical or verbal or non-verbal action. Also, during lethal events, it was less likely that deescalation by third parties occurred than during nonlethal events.

More precisely, in almost two-thirds of lethal cases involving de-escalation, third parties physically tried to separate the victim and offender or attempted to physically stop the offender, whereby some were injured themselves or became so afraid that they fled. In nearly 20 percent of cases, the third party either tried to verbally calm down the offender and victim or tried but failed to take away the offender’s weapon.

In over 60 percent of the non-lethal cases involving deescalation, third parties physically came between the victim and offender and tried to physically stop the offender from further attacking the victim. For example, third parties tried to stop the altercation by using physical violence against the offender, pulling away the victim or getting the victim inside, using a weapon or taking away the offender’s weapon, or coming to the victim’s assistance. In the remaining cases, third parties screamed or tried to mediate verbally during the conflict.

In half of the lethal cases involving escalation, third parties joined the fight by responding with physical violence themselves, whereby some also delivered insults, participated in pursuing the victim, threatening with a knife, or preventing the victim from escaping(e.g., by causing the victim to trip and fall during an escape attempt). In about a third of the cases, a third party either provided the offender with a firearm, held the victim so that the offender could stab the victim, or spat in the offender’s face.

In roughly 60 percent of non-lethal cases involving escalation, third parties joined the violence, called names, made provocative comments, or instigated one of the main parties to retaliate. In the remaining cases, third parties prevented the victim from fleeing. In a small number of cases, the type of escalating action was unclear.

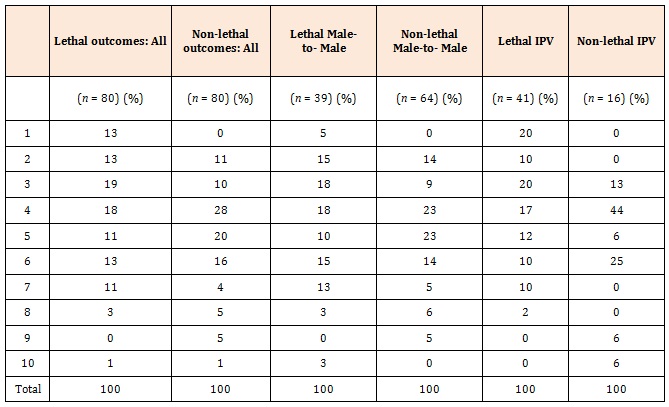

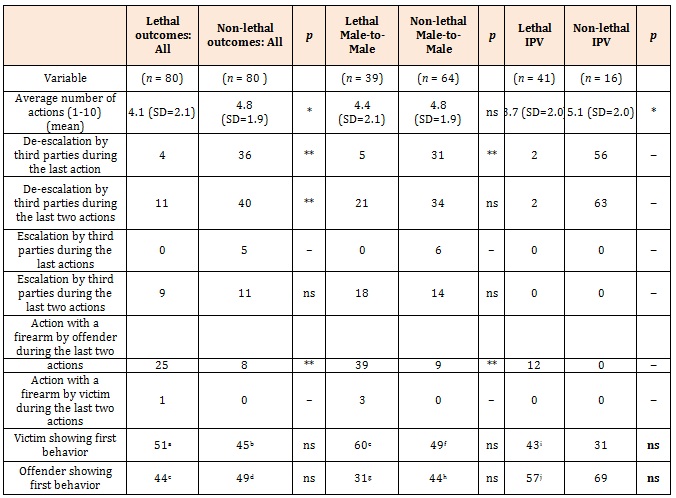

Sequential Characteristics In Lethal Versus Non-Lethal EventsTables 3 and 4 present the number of actions and the sequential characteristics during lethal and non-lethal events. Compared to non-lethal events, during lethal events: (a) the total average number of actions was lower, (b) third parties were less likely to de-escalate during either the last or last two actions, and (c) offenders were more likely to display or use a firearm during the last two actions (Table 4).

Sequence of Actions in Lethal Versus NonLethal EventsFinally, the sequence of events (Table 5) offers insight into how violent events unfolded. The sequence of events in both lethal and non-lethal events was quite similar and can roughly be summarized into the following stages: verbal or non-verbal actions– physical actions – deescalation by third parties and offenders’ action with a weapon (or vice versa). Similarly, if the victim performed an action with a weapon, this typically occurred before physical violence or the offender’s action with a weapon. Escalation attempts by third parties typically took place while the victim and offender were physically fighting each other. The results also indicate that – in contrast to hypothesis 1a – an action with a weapon by the victim did not occur sooner in the sequence of actions in lethal cases than in non-lethal cases.

Table 5 also indicates differences concerning the order of (a) escalation and (b) de-escalation by third parties. While in both types of violent cases, escalation by third parties took place as the victim and offender were physically fighting each other, escalation by third parties occurred sooner in the chain of lethal events compared to non-lethal events (in line with hypothesis 1b). Also, the sequence of events near the end of the chain appeared to be particularly distinctive with regards to the timing of de-escalation by third parties and the offender’s action with a weapon. In non-lethal events, de-escalation by third parties took place after the offender showed an action with a weapon, while in lethal events the sequence was the reverse order. Thus, de-escalation by third parties occurred later in the sequence of non-lethal cases than during lethal cases, a finding that is contrary to hypothesis1c.

Different Subtypes of ConflictTo examine the second research question and associated hypotheses, we investigated the type and sequence of actions in different subtypes of conflict. Type of actions across subtypes of conflict: Cases of male-to-male violence and cases of male-to-female intimate partner violence were found to be distinctive, particularly regarding offenders’ actions with a firearm and de-escalation and escalation by third parties. Table 2 shows that escalation by third parties and an action with a firearm by offenders more often occurred in both types of male-to-male cases than in both types of male-to-female intimate partner violence. Furthermore, de-escalation by third parties and verbal or non-verbal actions by offenders were more common in cases of male-to-female intimate partner violence than in the other types of cases.

Sequential characteristics across subtypes of conflict:Furthermore, differentiating between male-to-male cases and male-to-female intimate partner cases with a lethal versus non-lethal outcome showed that several sequential characteristics were distinctive, particularly regarding deescalation by third parties and if the victim or offender showed the first action (Table 4). More specifically, compared to the other types of cases, de-escalation by third parties occurred more often during the last or last two actions of non-lethal cases of male-to-female intimate partner violence. However, compared to both types of male-to-female intimate partner violence cases, third parties were more often found to escalate during the last two actions of both types of male-to-male cases. Offenders of both types of male-to-male cases were less often the one who showed the first action than offenders of both types of male-to-female intimate partner violence cases. Lethal victims of male-to-male violence were more often found to initiate the first action than victims involved in the other cases. Finally, compared to offenders of nonlethal male-to-female intimate partner violence, offenders of male-to-male violence and lethal male-to-female intimate partner violence more often showed an action with a firearm during the last two actions.

Sequence of actions across subtypes of conflict:Subsequently, we examined the sequence of actions in different subtypes of conflict to test our hypotheses regarding (a) physical violence, (b) actions with a weapon, (c) escalation, and (d) de-escalation by third parties. Table 5 shows that the sequence of actions differed between the subtypes of conflict, especially concerning (a) victims’ actions with a weapon, (b) escalation, and (c) de-escalation by third parties. In testing our hypotheses, the results showed – in line with hypothesis 2a and 2b – that physical violence as well as an action with a weapon (by either the offender or victim) emerged sooner in the interaction sequence of male-tomale violence than of male-to-female intimate partner violence. Also, in line with hypothesis 2c, female victims of intimate partner violence showed physical violence later in the sequence compared to male victims of maleto-male violence. However, the result does not provide support for hypothesis 2d that escalation by third parties occurs sooner in the interaction chain of male-to-male cases than in cases of male-to-female intimate partner violence. Note that that escalation by third parties was rare in male-to-female intimate partner violence cases. Finally, in testing hypothesis 2e, the results showed that de-escalation by third parties did not occur much later in the sequence of cases of male-to-female intimate partner violence than male-to-male cases. Thus, no support was found for hypothesis 2e.

Conclusion and DiscussionEven though the dynamic nature of violent events has been recognized for several decades, the actual interaction that takes place during lethal and non-lethal events has been understudied in violence research. To broaden current knowledge on the unfolding of violent events, this study investigated (a) what types of action and sequence of actions during violent events lead up to a lethal or a non-lethal outcome, and (b) how the type and sequence of actions differ across certain subtypes of conflict (i.e., male-to-male violence and male-to-female intimate partner violence with a lethal or non-lethal outcome).

Through a detailed examination of court files, this study has shown that lethal and non-lethal violent events unfold through the following stages: verbal or non-verbal actions– physical actions– de-escalation by third parties and offenders’ action with a weapon (or vice versa). If the victim performed an action with a weapon, this typically occurred before physical actions or the offender’s action with a weapon; and escalation attempts by third parties typically took place while the victim and offender were physically fighting each other. The present study demonstrates that the outcome of violent events is often related to the dynamic interaction pattern that takes place between the offenders, the victim and third parties, which is largely in line with Luckenbill’s situated transaction theory. However, whereas Luckenbill only looked at lethal violence and did not take into account that third parties can also de-escalate in lethal events, our study shows, in line with Felson and Steadman, that third parties can play a role in both lethal as well as non-lethal violent events and that they can intervene in both an escalating and a deescalating manner. Hence, this study demonstrates the important finding that third parties have an impact on serious violent outcomes, and therefore calls for more research on the role of third parties in serious violence. One of the study’s key findings is that it not only matters whether third parties intervene during the conflict, but more importantly, how and when they intervene during the escalation process.

The present study suggests that third parties’ intervention could be a critical factor in preventing a conflict from turning lethal. The importance of their intervention is illustrated by one of the cases from our files, a case of A (female) and B (male) who are intimate partners and are arguing about ending their relationship in front of their three children. For these kinds of cases, the third party’s role appears to be essential to preventing a potentially lethal outcome of a violent event. The presence of third parties does not necessarily guarantee a de-escalation of the conflict, however: the three children of the offender and the victim remained inactive, presumably because they were too young. However, two neighbors eventually intervened and saved the victim’s life:

Non-lethal case no 13:

Picture 1: In their house during the night, A (32) and B (43) – who are intimate partners – are arguing in front of their three children about the fact that A wants to end the relationship and demands that B leaves the house. A gets out of bed and suddenly B pulls A back by her hair while A is physically resisting the violence used against her.

Picture 2: While A shows physical resistance, B yells in the presence of their children, with a knife in hand, that he will not let her live anymore.

Picture 3: As A shows physical resistance and their children are witnessing the violence, B tackles A whereby A falls over on the ground. Then, A begs B to stop.

Picture 4: While their children are watching, B cuts A along the throat and A repels the knife attack.

Picture 5: While A is still physically resisting, B cuts one more time along A’s throat. However, because two neighbors intervene, A manages to escape.

The example illustrates how third parties can influence the outcome of a violent event. Further research and more detailed analyses are needed to find more conclusive answers, but we call for more attention to be given to the role of third parties.

Not all of our hypotheses were supported in this study. For example, one of the key elements distinguishing the sequence of lethal events from non-lethal events concerns the specific moment at which third parties de-escalate the conflict during the chain – which also holds when taking into account the subtypes of conflict. However, as opposed to what we hypothesized, third parties’ attempts to de-escalate typically occurred sooner during lethal events than during non-lethal violent events. Secondly, Felson and Steadman found that escalation and deescalation occurred before the stage of physical violence, while in both lethal and non-lethal violent events we found that these types of action occurred afterwards. Also contrary to what we expected, an action with a weapon by the victim did not occur sooner in the sequence of lethal cases than during non-lethal cases. More precisely, in the sequence of lethal male-to-male cases, victims’ action with a weapon occurred later in the chain compared to non-lethal male-to-male cases. There were not enough cases to test this in male-to-female intimate partner cases. This sequence of actions may indicate that male offenders and male victims involved in lethal violence tend to resolve the conflict by physical means first, while victims of non-lethal male-to-male violence tend to show more aggressive action sooner (i.e., displaying a weapon). It is possible that other (situational) factors not included in this study may play a role here. This clearly calls for a more research on this point.

Most of the hypotheses regarding the sequence between subtypes of conflict were supported. However, contrary to our expectations, de-escalation by third parties did not occur much later in the sequence of cases of male-to-female intimate partner violence than male-tomale cases. However, when taking into account whether the outcome was lethal or not, third parties’ de-escalating attempts occurred sooner during the sequence of both subtypes of lethal cases than of both subtypes of nonlethal cases. This suggests that, in these cases, third parties’ de-escalating intervention was unable to stop the offender from killing the victim. What remains unclear, though, is why de-escalation by third parties typically occurs sooner during lethal events than during non-lethal violent events. This is a limitation of considering only the actions or behaviors of third parties, and not their cognition. For example, in considering the cognition of third parties, third parties might be able to make judgments on when to intervene – either sooner or later, and in some cases, these judgments could be based on prior experiences. Not considering the cognitive aspects of third parties is therefore a limitation that future studies should address.

All in all, although some questions remain open, this study has contributed to the sequential literature on violence by showing not only that violent events pass through several sequential stages, but moreover, that the sequence in lethal versus non-lethal violent events differs, particularly with regard to when third parties de-escalate the conflict. While Luckenbill did not address deescalating action by third parties, this study suggests that de-escalation by third parties may be a critical factor in how events evolve. This result is an important finding, as previous studies rarely focused on how third parties shape a lethal or non-lethal outcome of violent events. Third parties clearly deserve more attention. We have also demonstrated the added value of distinguishing certain subtypes of conflict (and their outcomes) in order to highlight important differences with respect to (1) when de-escalation by third parties occurred, (2) if and when third parties escalated, and (3) if and when the victim showed a weapon during the chain.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future StudiesWe are aware that our research also has limitations. First, the study investigated a relatively limited selection of one-on-one cases registered in two main court districts in highly urbanized areas in the Netherlands. Therefore, further work needs to be carried out to assess whether these results also hold for cases involving multiple offenders and/or multiple victims, and in other localities. Also, the relatively small sample size limited our statistical analysis, especially with regards to non-lethal male-to-female violence. Moreover, since the current study primarily relied on data from court files, we encourage future studies to enhance their validity through a triangulation strategy and, if possible, by integrating interview data. The use of interview data would also enable researchers to capture reasoning, cognitions, and perceptions of the involved parties that can help to understand more fully why they exhibit certain actions. Also, since the focus was on the interaction sequence, little attention was paid to the prior (interaction) history between the offender and the victim, which may distort the picture in cases with a longer runup. For example, a possible reason for why lethal intimate partner violence has fewer actions than all others is the longer history or longer build-up: intimate partner violence is often progressively violent over time. Future studies may overcome this by using Calendar History data. In addition, some possibly important situational and control variables were not included in this analysis, such as public versus private places and alcohol use. Another recommendation for future research is to carefully consider how third parties’ cognition and their characteristics matter, and especially their age, sex, size/posture and relationship to the offender and the victim. For example, a question worthwhile to consider is whether it makes a difference if the third party is a male or a female, in a male-to-male conflict or a male-to-female conflict [43,44].

In sum, more work has to be done to enhance our understanding of the mechanisms leading to a lethal outcome of violent events. However, the present study has demonstrated not only the importance of comparing situational dynamics of different subtypes of conflicts and their outcomes, but also that it is essential is to take into account all parties present. Ideally, interaction chain analyses could even inform anti-violence policies in the future.

Table 1: Background characteristics of offenders and victims involved in lethal and non-lethal events.

Note: amissing = 1; bmissing = 1; cmissing = 9; dmissing = 5; emissing = 13; fmissing = 8; gmissing = 4; hmissing = 4; imissing = 1; jmissing = 1; kmissing = 5; lmissing = 4; mmissing = 5; nmissing = 4; omissing = 10; pmissing = 6; qmissing =4; rmissing = 4; st-test; tmissing = 4; umissing = 1, t-test; vmissing = 4; wmissing = 1; xmissing = 3; ymissing = 2.

*p < .05;**p < .01; ns, not significant

Table 2: Type of actions during lethal and non-lethal events.

Table 3: Total number of actions during lethal and non-lethal events.

Table 4: Sequential characteristics during lethal and non-lethal events.

Note. amissing = 8; bmissing = 7; cmissing = 8; dmissing = 7; emissing = 4; fmissing = 7; gmissing = 4; hmssing = 7; imissing = 4; jmissing = 4

*p < .05;**p < .01; ns, not significant

Table 5: Sequence of actions during lethal and non-lethal events.